A friend of mine called me up last week and asked if I wanted to get a coffee and look at North Korea. A Starbucks has popped up at the bleeding edge of capitalist expansion, about an hour’s drive from where I sleep at night. “It’s like -10°C, so… you’re buying lunch too.”

We took my little van through Paju’s icy passes, stopping occasionally to photograph this or that, and eventually made our way to a well above sea-level car park with snaking lines of latte devotees. We thought we’d be alone. Two queues later - one of them twice - we hopped a bus for the summit. A boy-soldier checked everyone’s tickets but ours, figuring, I guess, that we were either not a threat or sufficiently bilingual.

The weight of the bus driver’s foot on the accelerator suggested he’d slung these curves a thousand times or more, and we whipped to the top in no time at all. The top consisted of a few empty parking spaces, a forgettably designed government building and a line of people for the bus back down and away from this place. Everyone went straight for the warmth behind the glass doors, but my friend and I puttered around a bit, checking out a memorial of a bayonet wielding soldier.

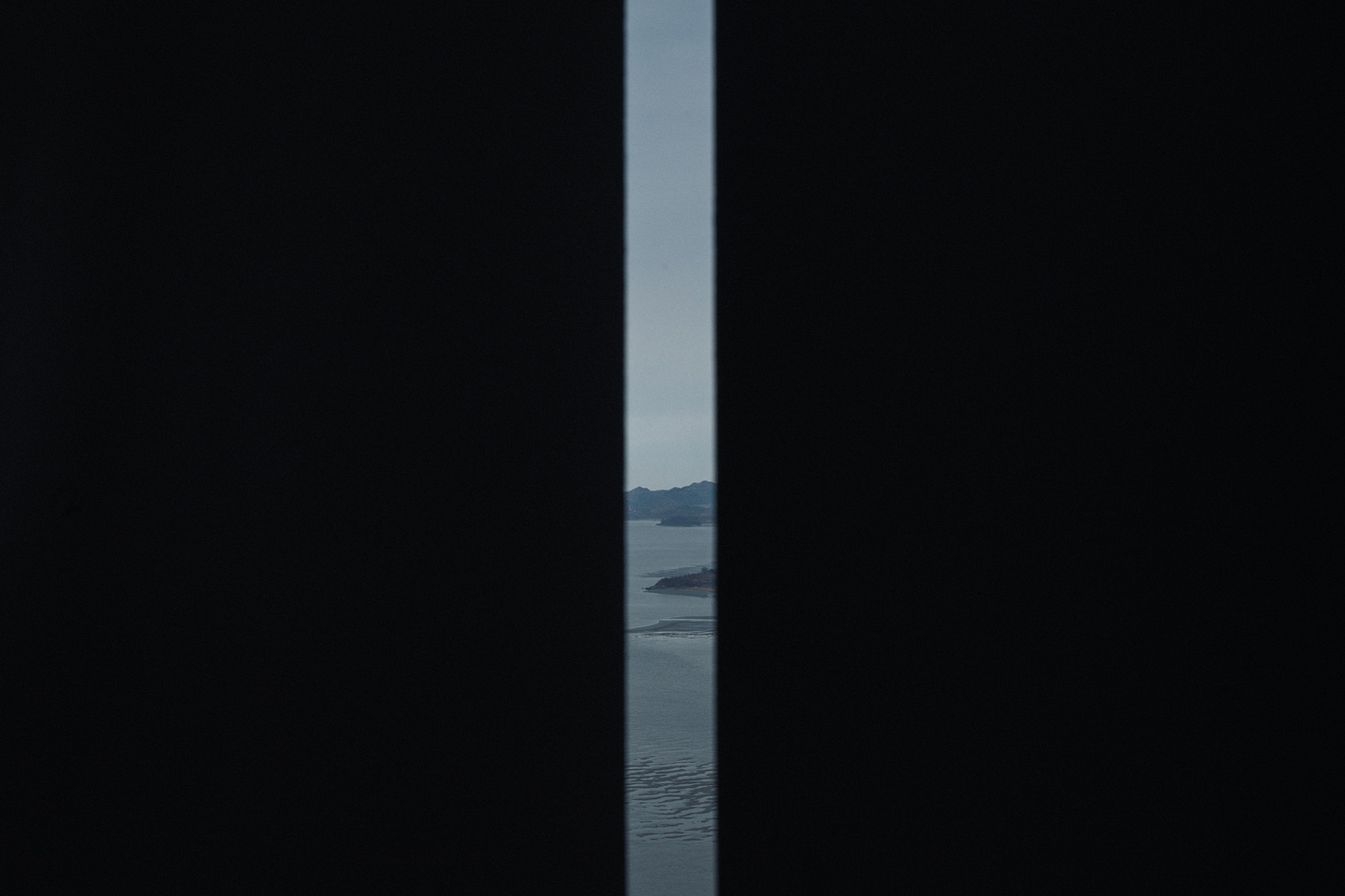

From the memorial we could see a great wheelchair ramp zigzag into the clouds, which parted to reveal the marine smirk of the coffee giant’s logo. The path lead us to a raised terrace, home to 6 or so floor-mounted binoculars, a jumble of coffee-clutchers and a peak behind the red curtain.

The situation in North Korea is uncomplicated in its awfulness, and this platform of sight-seers, as if the realities of that country were that kind of sight, just made me sad.

While my friend did his best to fit Capitalism and Communism within the same frame, I sat sipping my americano in maybe the bleakest Starbucks I’ve seen. People took selfies with their coffee cups in front of the North Korean vista, then in front of the Starbucks itself. Selfies that are meant to say what, I don’t know.

Through the cafe’s glass boundary separating the scene from me I saw a soldier step into view. Then another, and another. A squad coalesced into a platoon. Would ordering another cup muster a battalion in rank and file? I gave up our table to one of the many old people lurking by the shelf of commemorative mugs and stepped back into the cold and light.

I hadn’t been feeling very inspired - photographically I felt quite distant from this whole scene. But I’ve come to know well that the scene won’t change for me, unless I ask it too. One of the young soldiers pulled out a phone as two or three friends readied a pose. I walked over to him and asked fairly loudly in Korean, gesturing around,

“Are all of you friends?”

“We’re all from the same base.”

“Aren’t you cold in those clothes?”

”They’re alright.”

”Really? They look kinda thin and it’s pretty cold today.”

“Well, yes, they’re a little cold.”

“Ok. Well I’m probably going soon, but can I take a photo of you and your friends? Bring all of them over if you want.”

Asking a stranger for a photograph can be a daunting thing. Especially when that stranger is trained in combat, and even though he’s younger than you, could probably pin you quite easily, which would be embarrassing. I spoke to the private because I wanted to remind myself of something I’ve learned before, but often forget: Approaching a group for a photograph cedes your power as a photographer. In a good way.

Here’s what I mean. Asking a lone stranger for a photograph can put them on the spot. We as the photographer are in a position of power because we’ve initiated the situation. The person asked has only one way to exercise their power in return: saying ‘No.’ But when you approach a group, you demonstrate a willingness to invert that usual power dynamic - Here I am, alone, asking all of you in this big group to stand for me. You are in control, and you can feel at ease.

This, understandably, is often more uncomfortable for the photographer than it is for the subject. That’s the point. Showing that you’re OK with that dynamic puts the group at ease, or enough of the group, and you’re that much more likely to get the go ahead. Sometimes, all of this is simply a means of breaking the ice, forming those first tentative bonds of communication that allow for more, naturalistic photos to happen. Once the group has accepted you, you can go back to shooting candidly in a far more relaxed atmosphere. The group photo was your tacit permission.

Asking for photographs is a muscle that occasionally needs to be exercised. I still get that little rush before I ask. But that little rush is the indication that you’re dialed in, being active about the image you’re making, and trying something that might not work. That, I think, is how you make something that is worth the while.

Cheers,

Chris.

Man, I dig these. That last one...

So you're saying there's a Starbucks on a mountain summit / lookout purely to have a look at North Korea (with binoculars) ? And then I thought I heard a lot ... But yeah at least it makes for a good story 👍