I was 23 and climbing the first fire escape I’d ever been on. I was going up. It was a cool night in Tokyo, and there was a din of car- and foot-traffic gently receding below as I rose, transported squarely by spiral metal stairs. I was alone and had been for a few days, so, to entertain myself in the free way an enthusiastic but under-employed traveler might, I was going rooftopping. I can’t remember but I was probably wearing a too-tight-yet-still-cold pleather jacket I had bought to look cool for the trip. I liked to wear it with white socks, black skinnies and a white shirt until it was pointed out Michael Jackson wore it better. I was also probably wearing the Dr. Martens I’d bought on arrival (and still own) at a place where I don’t think I did the YEN→WON conversion quite right, and which were too new and toothy for serious walking. At a landing in the upper reaches I passed my first opened door, and, with exceptionalism, peeked inside.

Two men I curiously remember being dressed in black shirts and blue bandanas (though surely not) which for some reason made me think they were chefs (again, surely not) stood atop a horde of books and papers so high their backs were dipped and pressed against the ceiling. They were throwing the books into a smaller pile closer to the door. That pile was I guess the trash heap’s trash heap. The chef nearest, stooped and sweaty, turned his head to me, toes curled for purchase on the could-give-at-any-moment mound, and this I guess being enough, waited for me to respond. “Uh. Do you mind if I look through the books?”

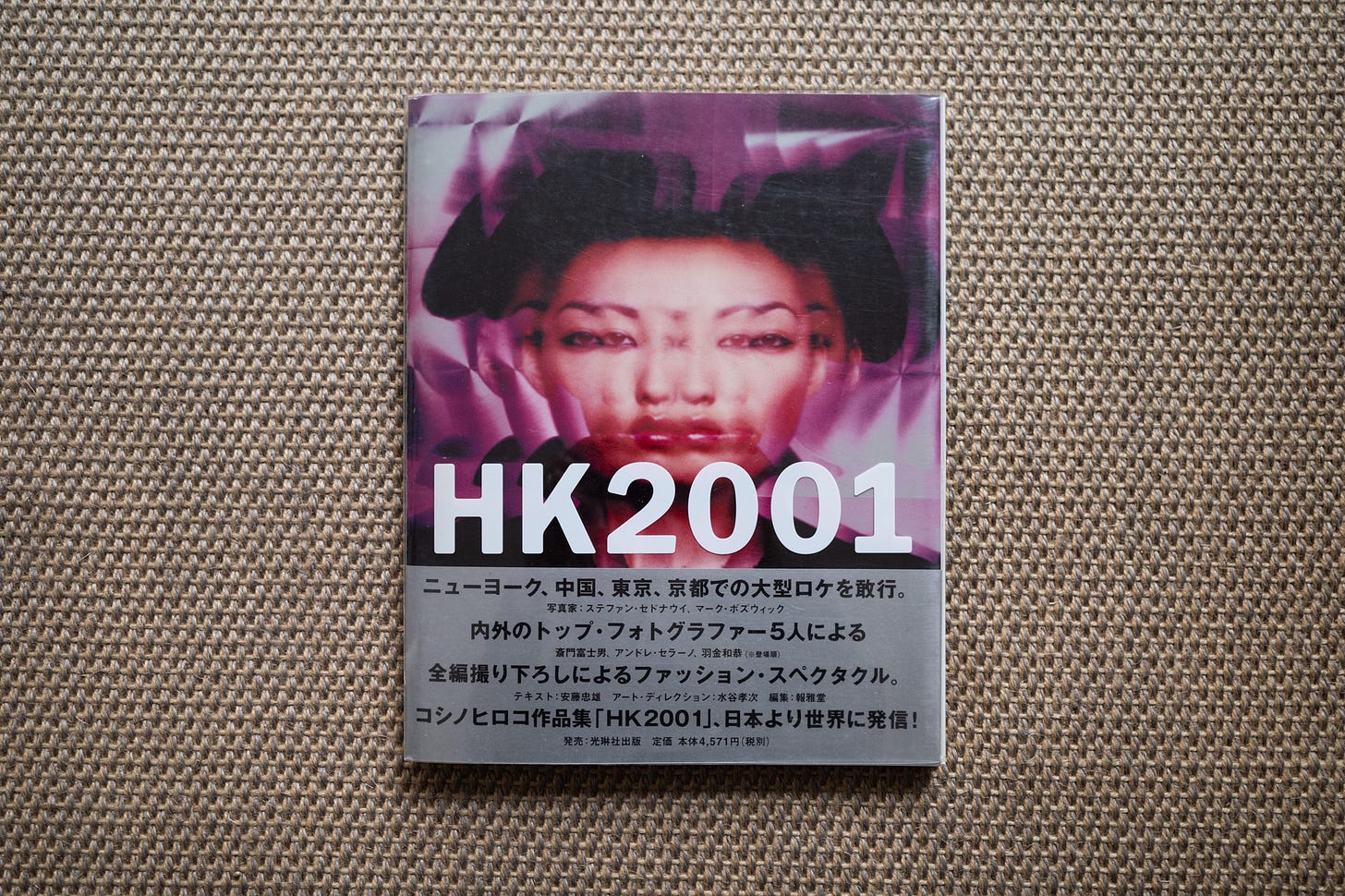

He must not have cared because I spent a fair bit of time stacking volumes to take home with me, home being one of those capsule things that sounded like a cool idea until I realized I had to leave all my stuff (like my new Dr. Martens) behind an unlockable wisp of curtain while I was out soaking up the sights, sounds and stairwells of Harajuku. Once I’d returned to the heap² a dozen or so mangas (of which I’d only ever seen one before growing up in Durban, not a mecca of Asian culture, in my high school’s library, and no sooner than I had figured out you read it back-to-front when two kids even less cool than me whose nonchalance was betrayed by shinily slavering lips came over to ask if I was planning to take it out. Yes, I was.) I set aside my little stack of tossed pearls: a few of the raunchier mangas and HK2001, my first photo book.

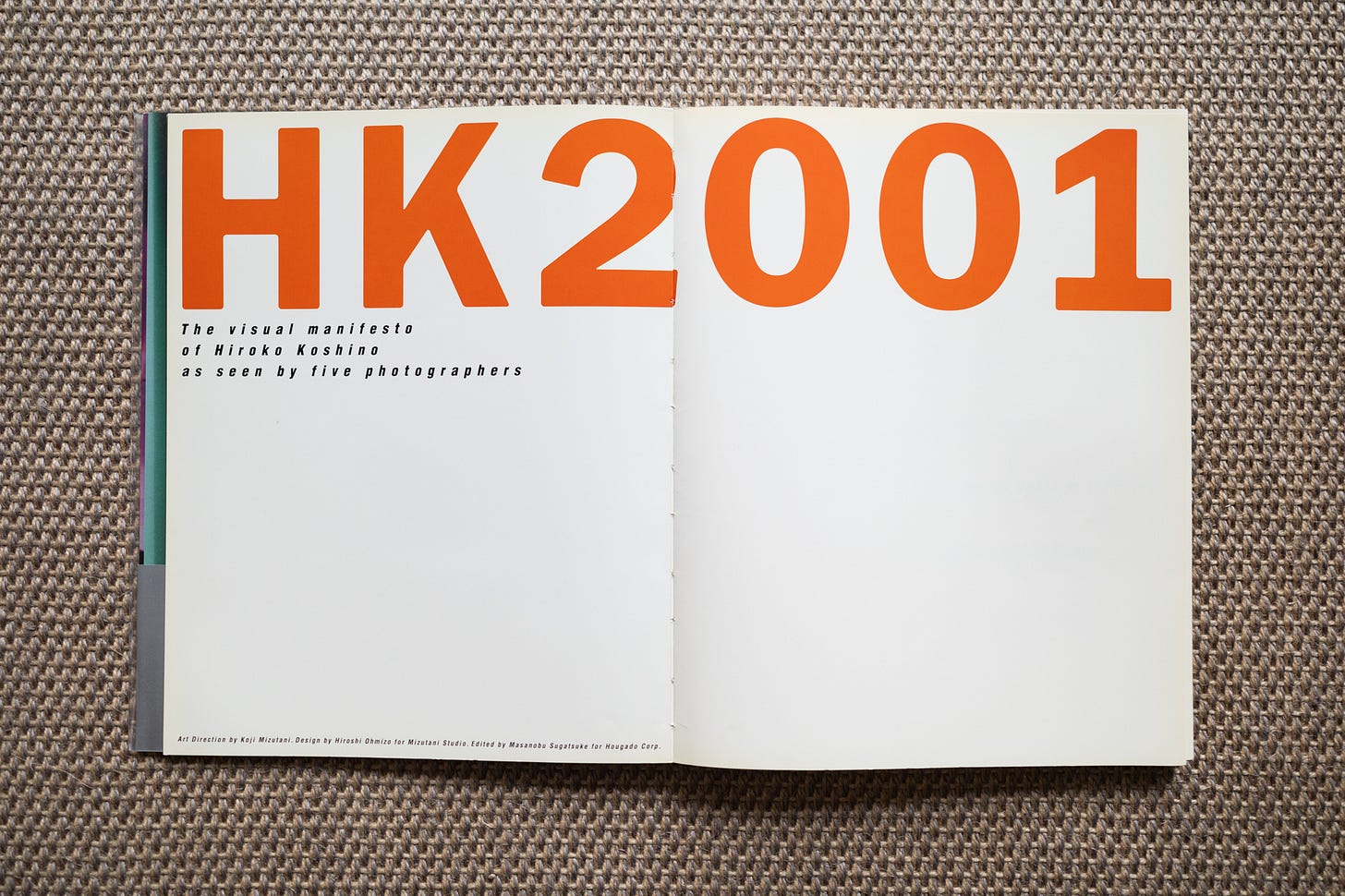

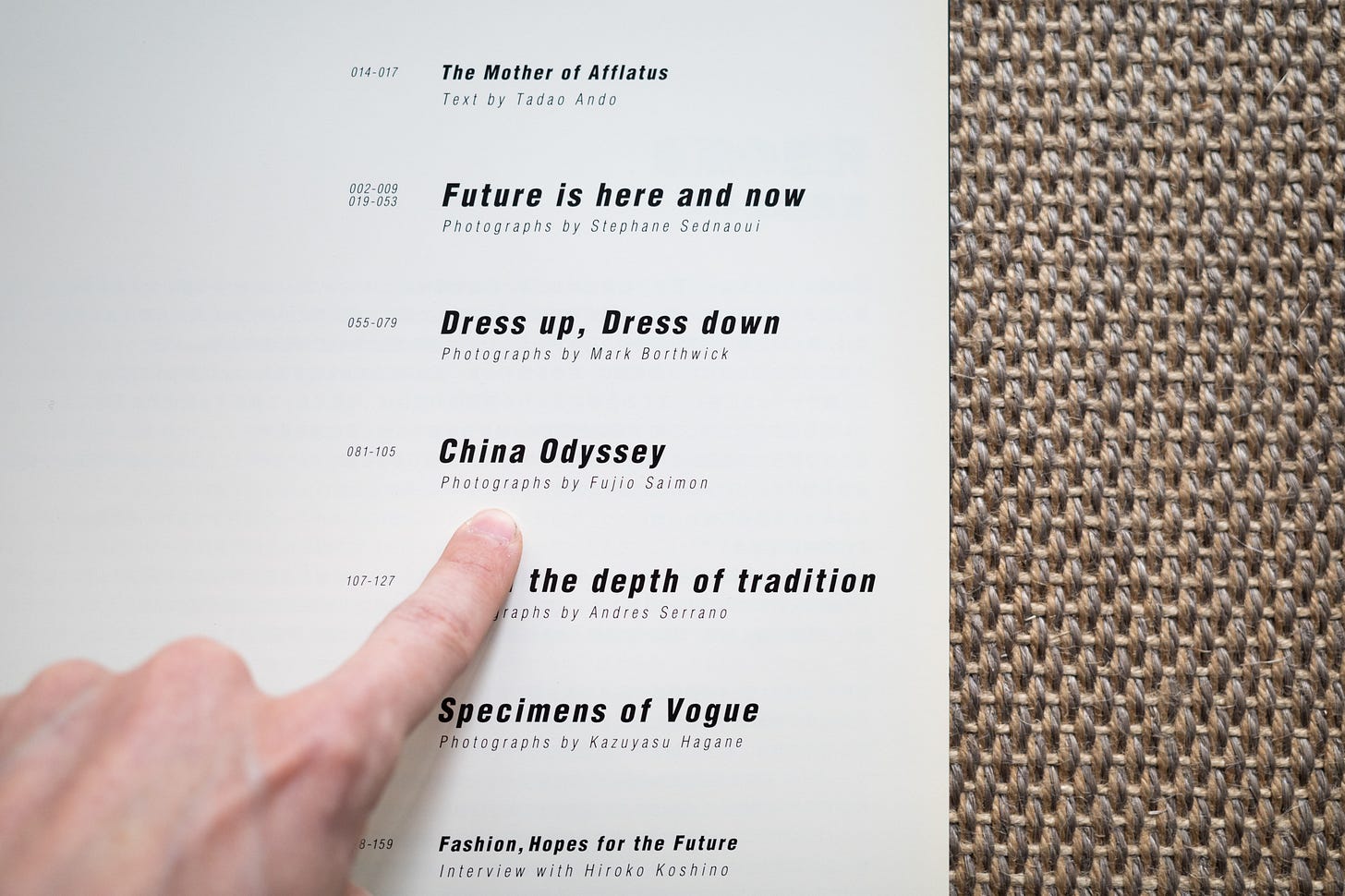

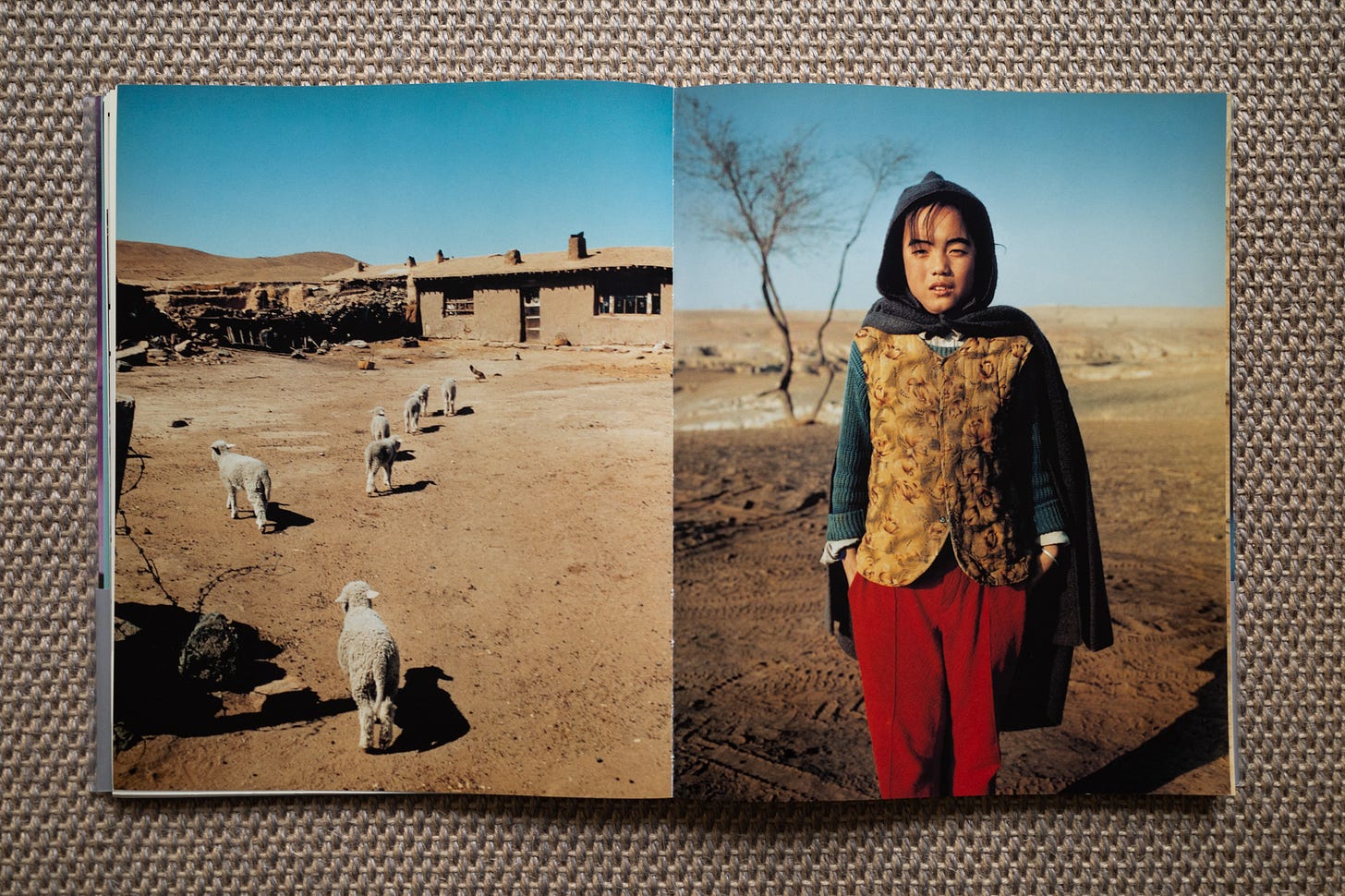

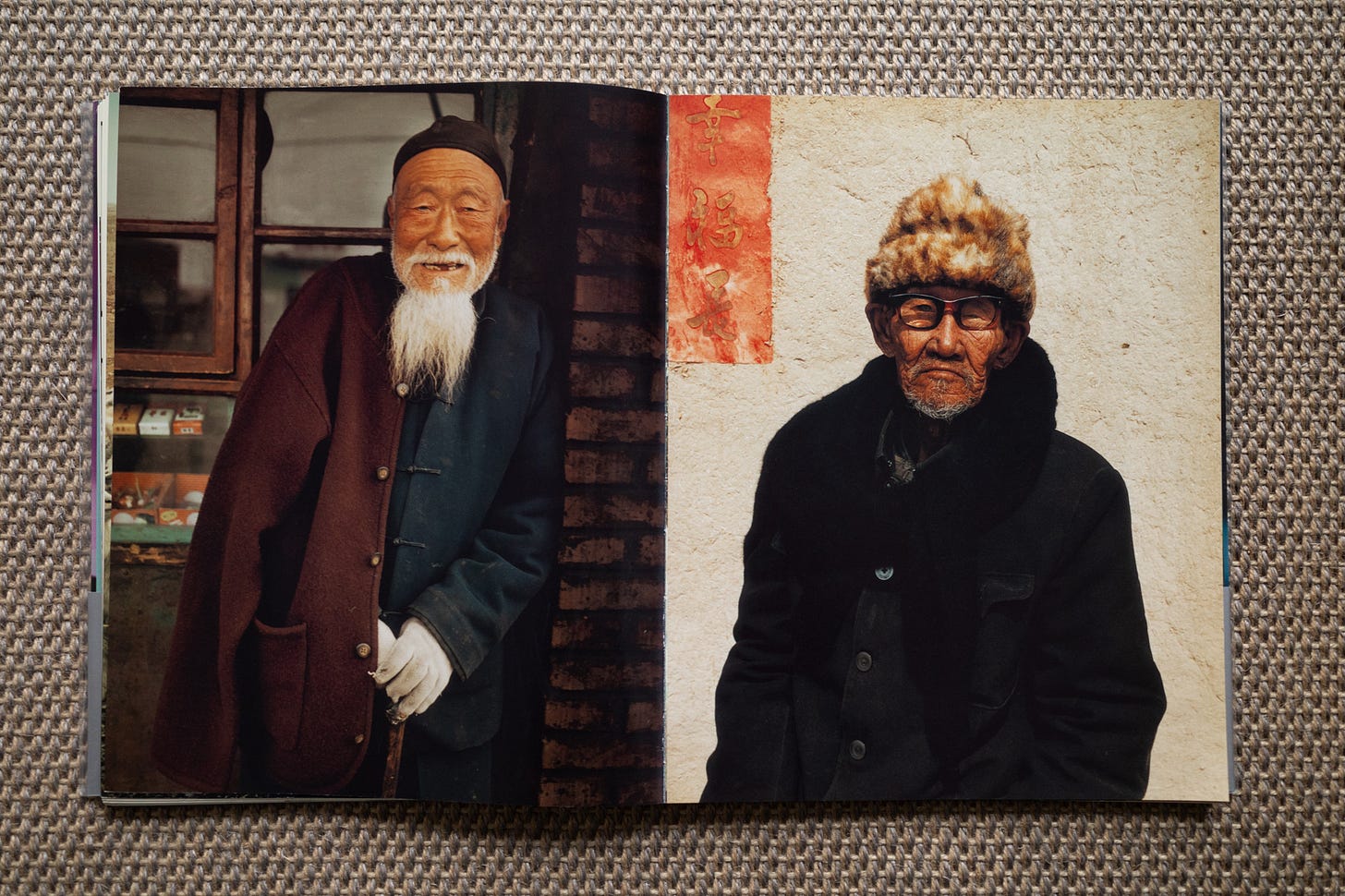

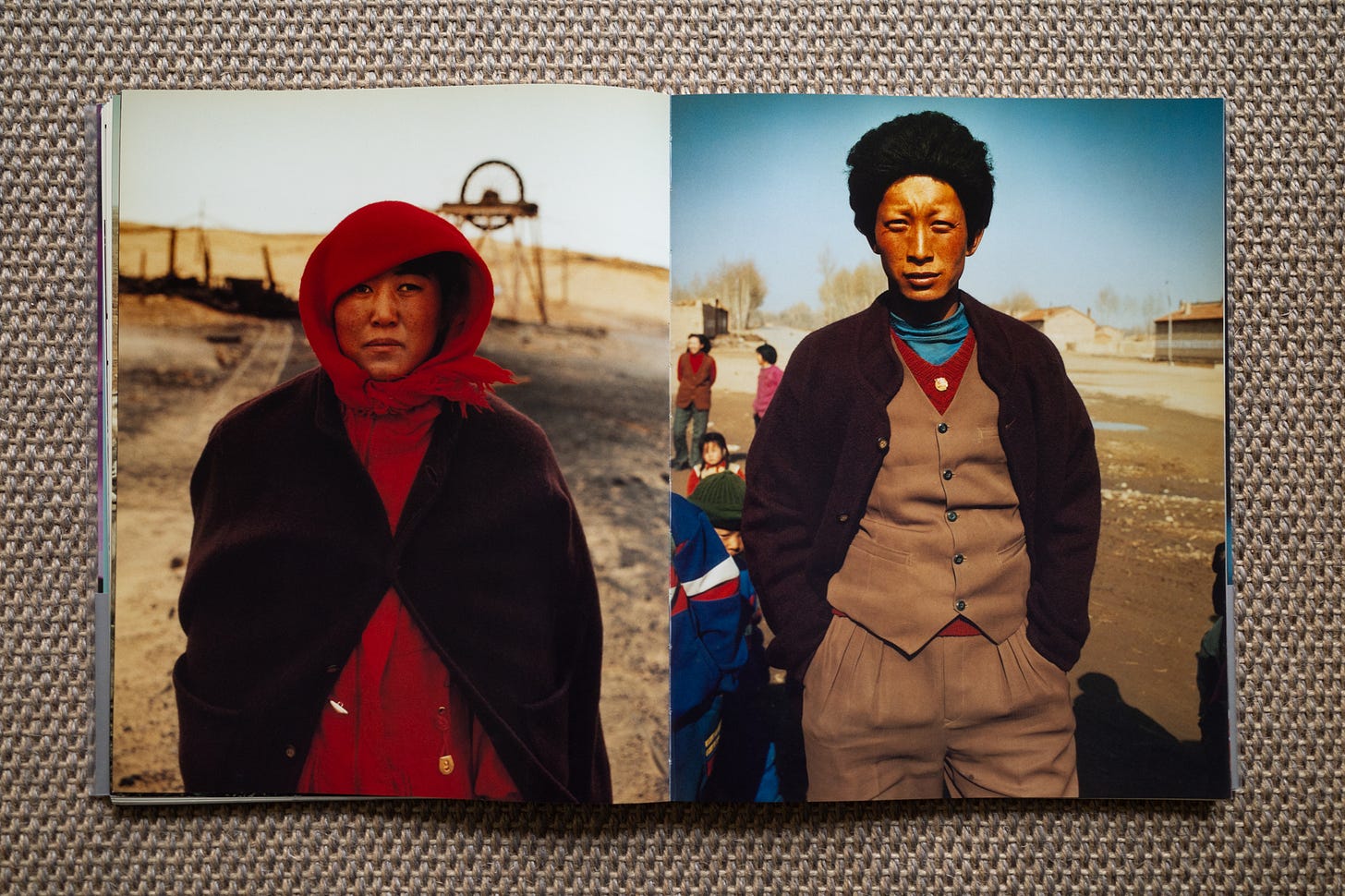

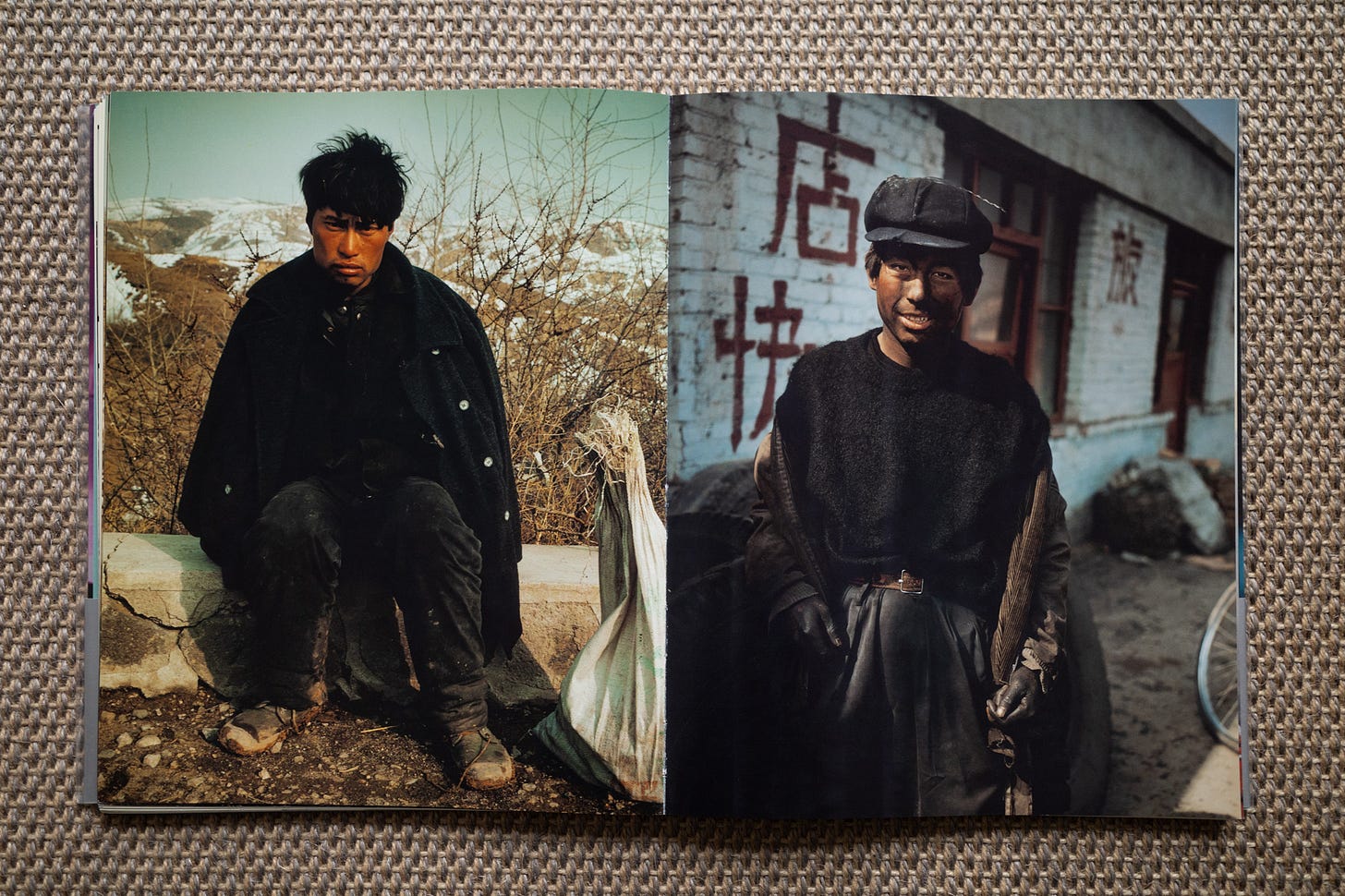

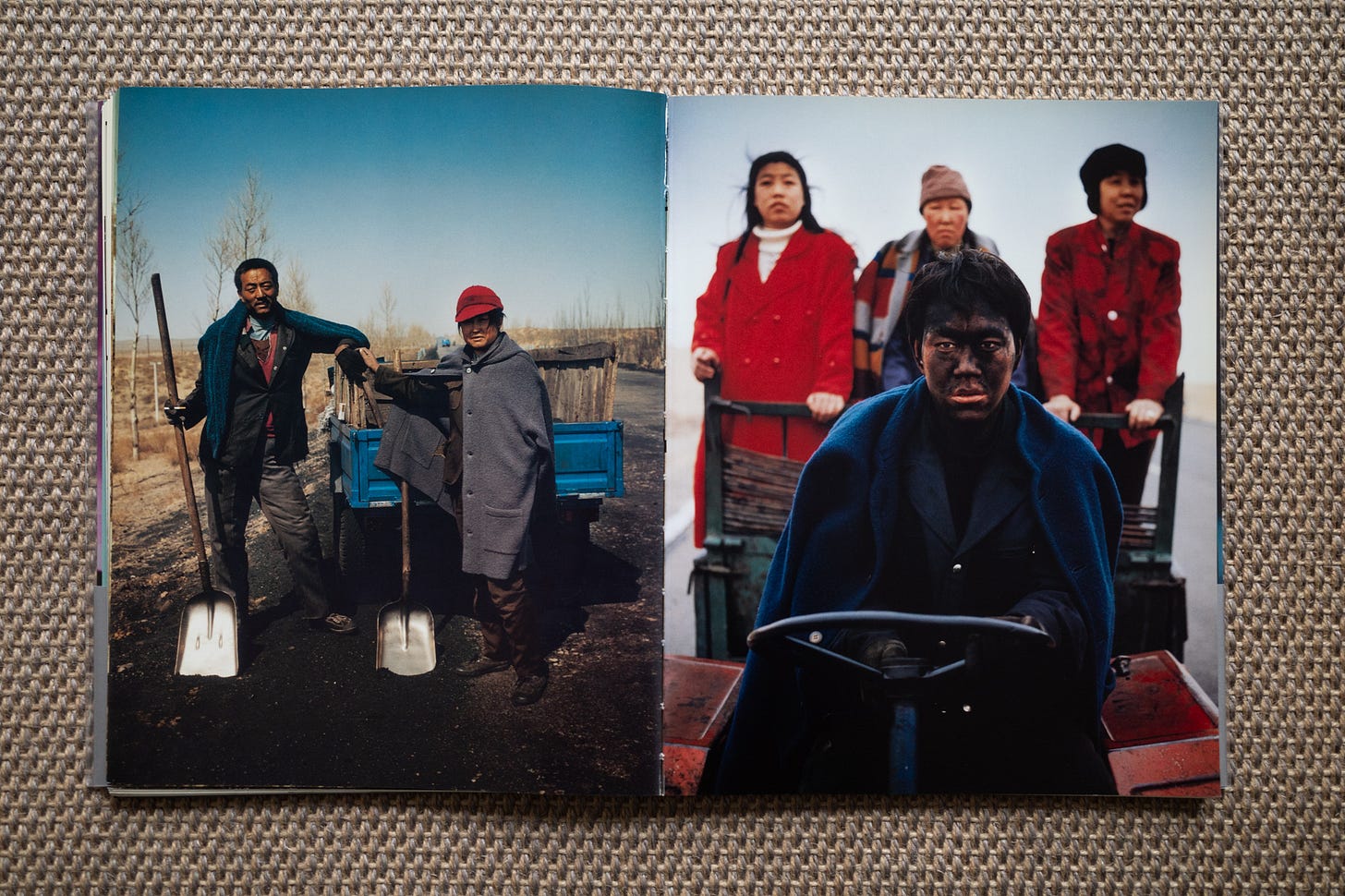

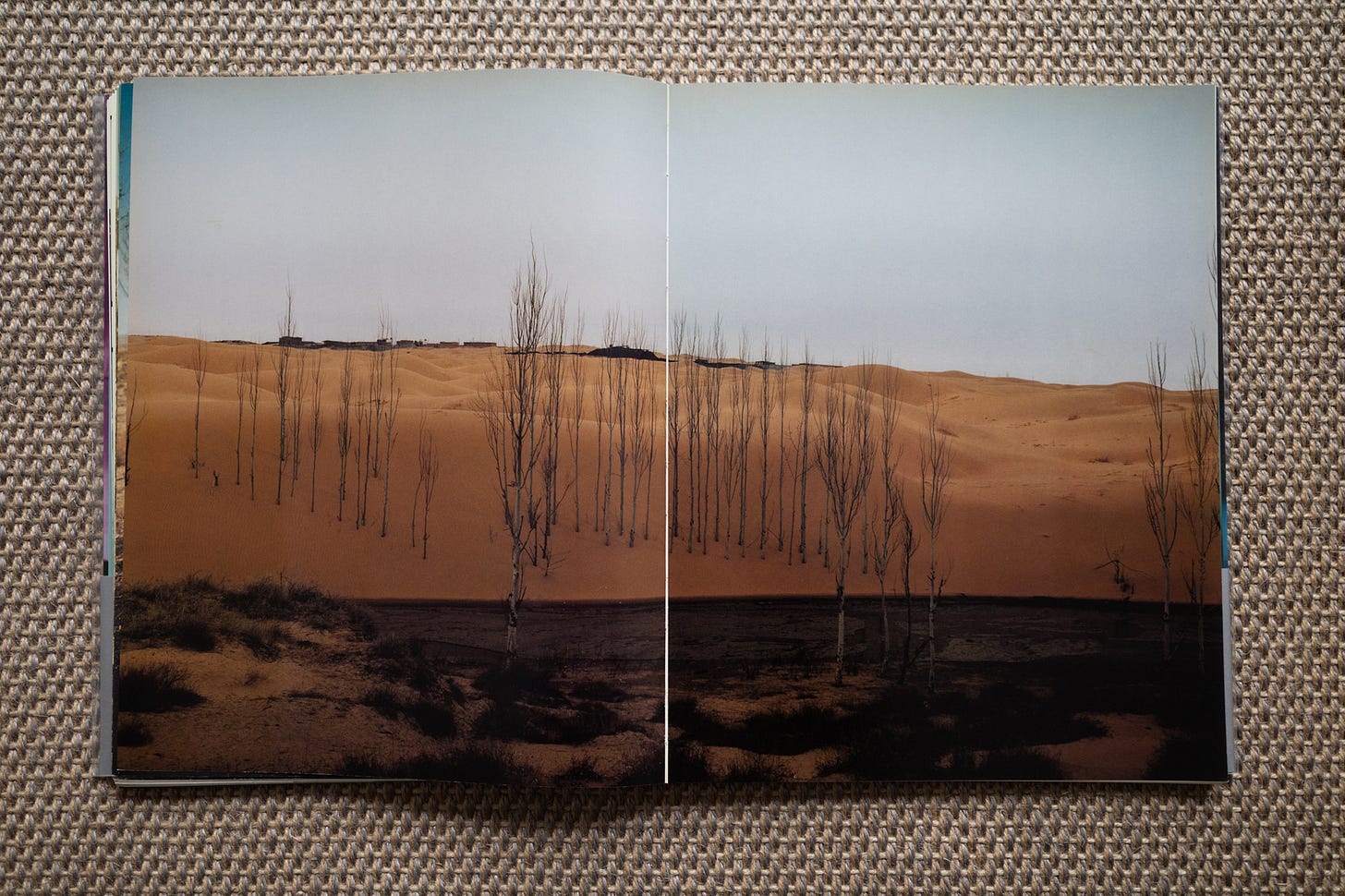

The book, it tells us in English, is a “…visual manifesto of Hiroko Koshino as seen by five photographers”. Koshino is a Japanese fashion designer whose accolades, according to her website, are so varied and impressive that I thought I’d be able to find at least one that would be kind of funny or odd, but instead I only found a dark reminder that other people have a much better sense of how to dedicate their time and be productive than I do. The 5 editorials in HK2001 are all pretty diverse, and while I like some more than others, it was China Odyssey by Fujio Saimon that secured ‘2001’s place under my arm as I plodded back to the surface streets.

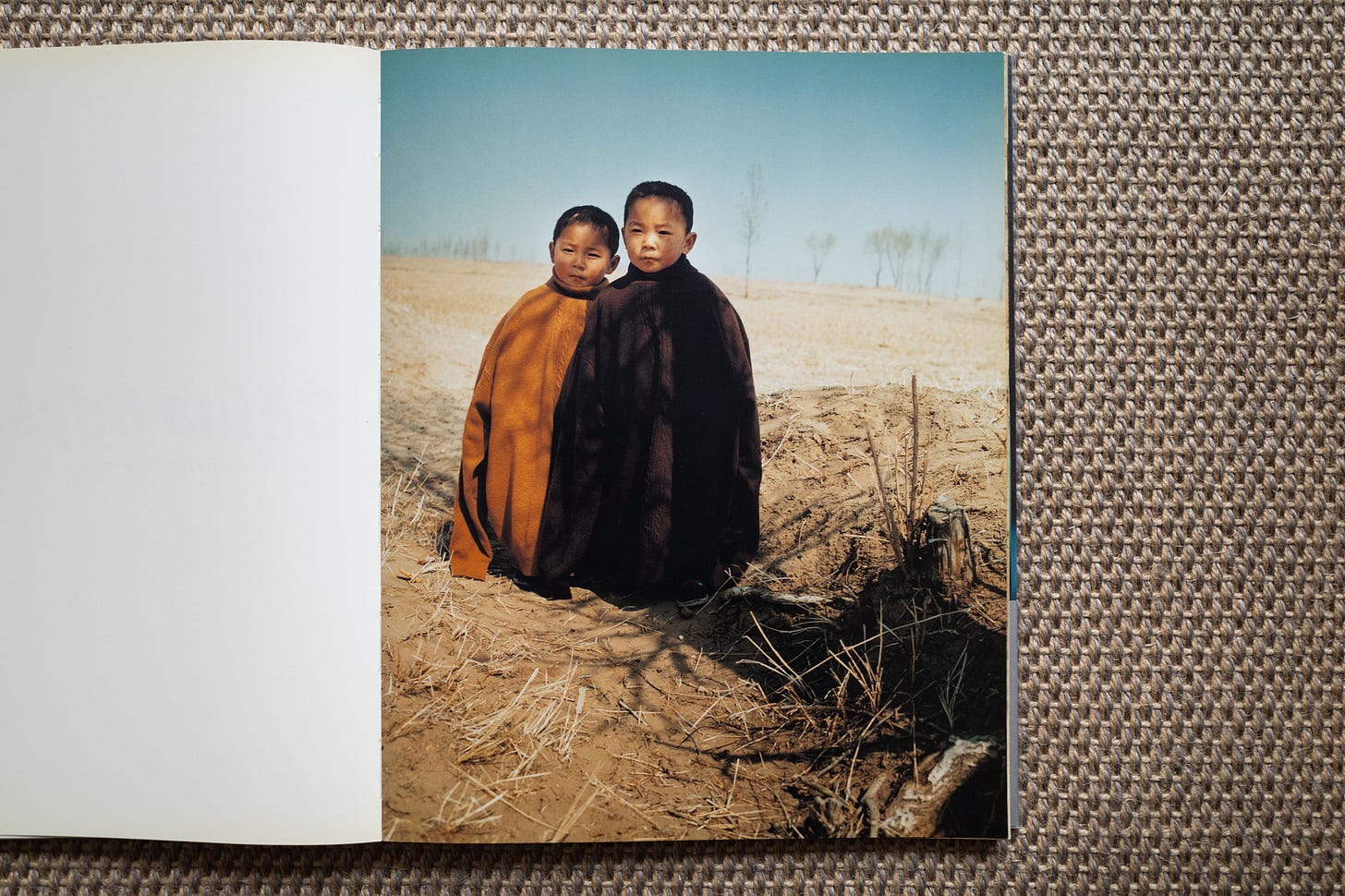

Saimon’s1 editorial was eye-opening for me. It was the first time I thought fashion photography looked cool. I studied ethnography at university (which now leaves me like, aghast) and I’m well enough aware that finding the very un-PC equivalent of a Chinese peasant and dressing them in high-end knits for the edification of a Japanese fashion magnate is potentially icky. But, then again maybe not, I don’t know all the details. All I was concerned with when I first saw these photos was how direct, how powerful they are. There’s something in the intro essay The Mother of Afflatus2 by architect (I think) Tadao Ando, which is about Koshino’s designs but I think better directed at Saimon’s editorial. To quote it at length:

The form of aesthetics which has been considered by most to be the most “Japanese” advocates the maintaining of nature in its untouched state, a conviction which could be described as Kinnari-no-bunka, or “Culture of rawness”. However, Kabuki3, which is conversely overflowing with fascinating and sometimes mysterious colors, rather than being a culture of calculated logic, also embodies a type of rawness, that is found in many people’s lives.

I’ve put the majority of the photos here for you below, but a handful will be kept between the sheets. It’s not an easy book to find but it is out there, along with Saimon’s other works (which I’ll share in time), and it’s worth seeing in person. Plus, now maybe Hiroko Koshino won’t send her dogs after me, because she seems just the type motivated enough to find this and yell ‘sic’.

In my annual search for new information on the photographer, I’ve seen him referred to as Fujio Saimon, Saimon Fujio, Hujio Saimon and once Fujio Saimon Mystro, which seemed fitting. I’ll refer to him as Saimon here.

Koshino’s professed influence. It’s interesting to think of China Odyssey in terms of Kabuki though, of which performance, tradition and stylization are all a part.